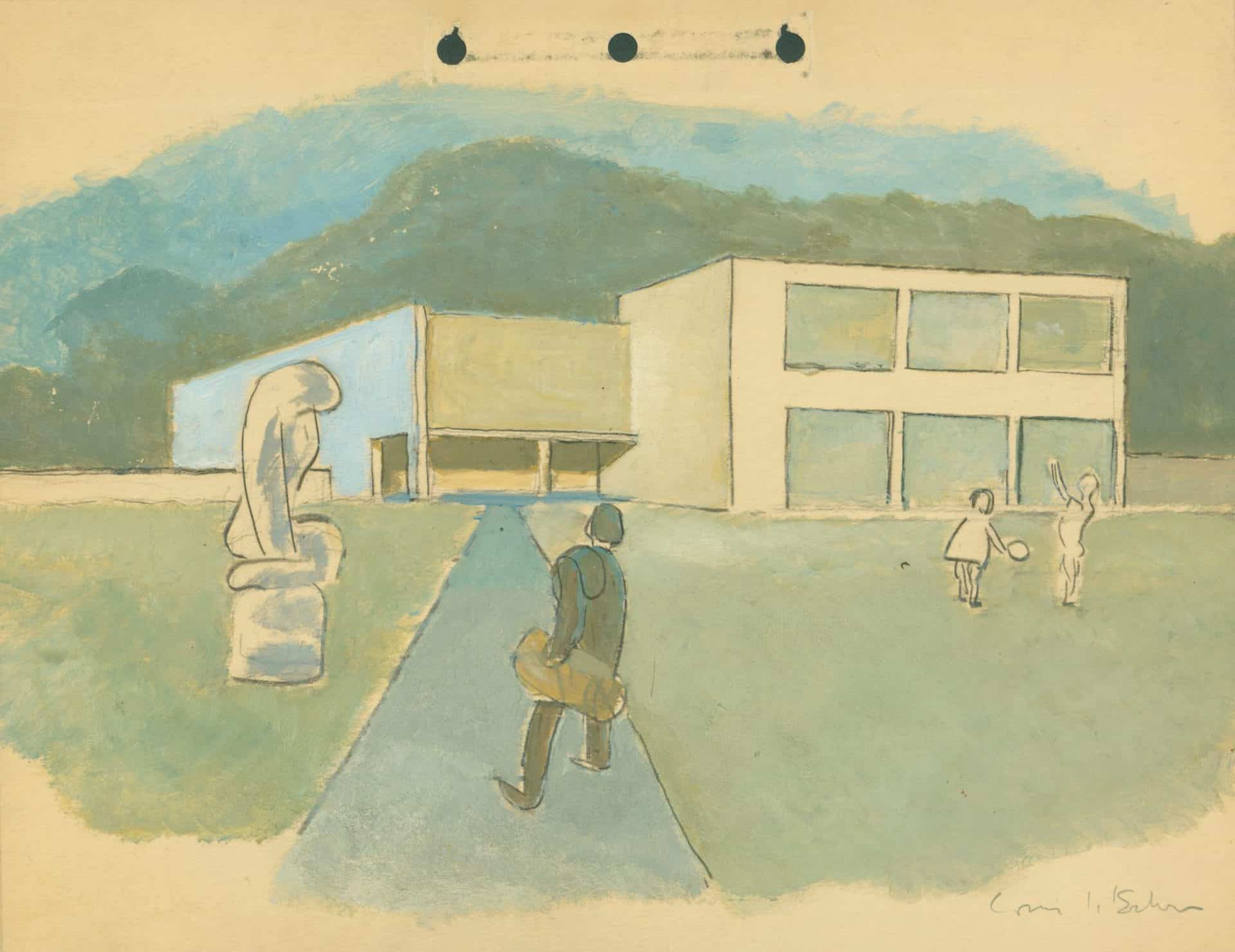

Image: Jersey Homesteads rendering, 1936, by Louis I. Kahn.

In the 1930s, America was in the midst of the Great Depression, but those dark days spurred a period of reinvention and reinvigoration. President Roosevelt’s New Deal created programs that reached out to workers and new immigrants. Artists were employed to document America and its people, and to ornament the new bridges, parks and buildings that were being constructed.

Planned communities sprang up across the country, including a very special one in the heart of Monmouth County, New Jersey. An exhibition at Morven Museum & Garden, “Dreaming of Utopia: Roosevelt, New Jersey” tells the story of a unique community that continues to thrive today, albeit not as the cooperative farm and factory town it was first envisioned to be.

Originally called Jersey Homesteads, Roosevelt was a town built for recent immigrants; many of which were garment workers. In this ideal cooperative community, they would live and work, making clothing from start to finish. The government-built houses were designed by Alfred Katzner and his assistant – the now revered architect Louis Kahn – who were both enamored with the Bauhaus style. They gave the modest houses high-end architectural elements unusual for the time, such as flat roofs and floor-to-ceiling windows.

However, by 1939, the cooperative had already failed, and the factory closed. This was the end of Jersey Homesteads’ first chapter, but its next chapter is what made the town more than just an historical footnote.

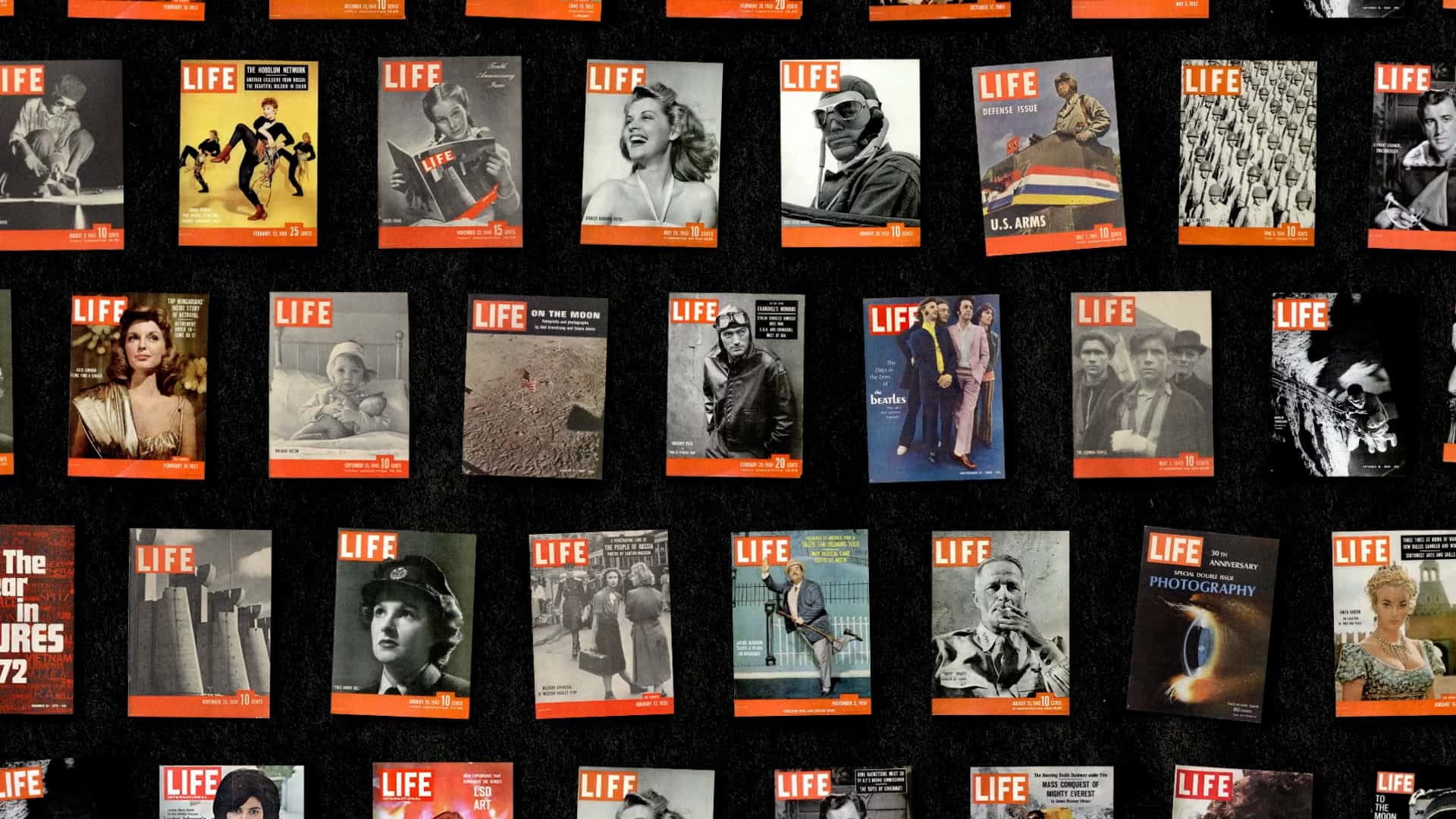

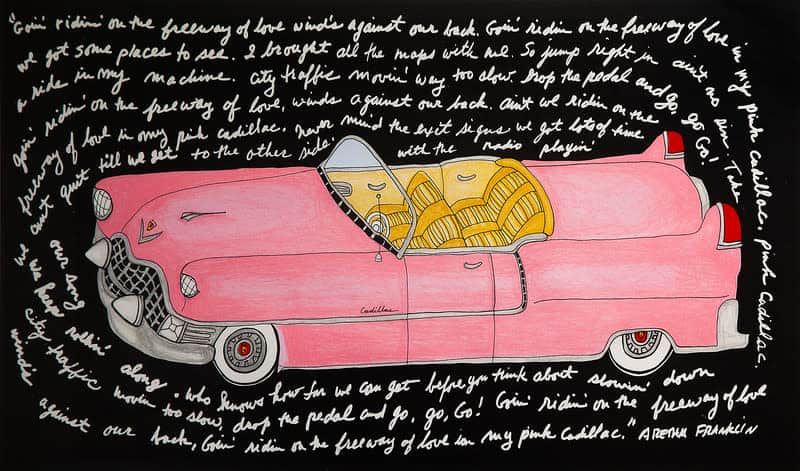

Artists began to move to Jersey Homesteads, renamed Roosevelt to honor the president after his death in 1945. These worldly, creative types appreciated the modern style of the houses, and the progressive nature of the town’s politics. Many had worked as artists or photographers for New Deal programs such as the Works Progress Administration and the Farm Security Administration. Their politics were progressive, and the town’s history appealed to them. These bohemians found community in Roosevelt, as well as open space for their young families and proximity to New York.

The first artists to discover Roosevelt were Ben and Bernarda Bryson Shahn. Ben Shahn was a rising star, on his way to becoming the most well-known artist in America by the 1940s. Bernarda Bryson Shahn was a writer, illustrator and painter. They arrived in Jersey Homesteads to paint a mural for the community center, which now houses the local elementary school. Their 12 x 45’ fresco mural can still be seen there. It tells the town’s story, from immigrants arriving in America, through the growth of the labor movement, to the founding of the cooperative, where farm and factory would support a decent life for workers.

After the grand experiment was called off in 1939, the government first rented, then sold off the houses. The Shahns were among the first to buy. They told their friends, and by the 1950s, there was a critical mass of artists in town. A new sort of utopia was formed, with artists playing a vital part in the small town (population about 800). Morven’s galleries include a wonderful selection of art by the first generation of artists to call Roosevelt home, including Jacob Landau, Edwin and Louise Rosskam, Elizabeth Dauber, Gregorio Prestopino, Sol Libsohn, and Ben and Bernarda Bryson Shahn.

Musicians and writers lived there as well, and the curators have included fascinating anecdotes and objects to tell their stories, including a reading nook with original editions by Roosevelt authors and illustrators. The label to “Woodwind Quintet” (1951), an ink drawing by Robert Emmett Mueller, quotes the artist, musician, and MIT-educated engineer: “Roosevelt was like one big open house in those days. You’d go somewhere to listen to folk music, then you would go to someone’s house for dinner, then to another house for a discussion on art.”

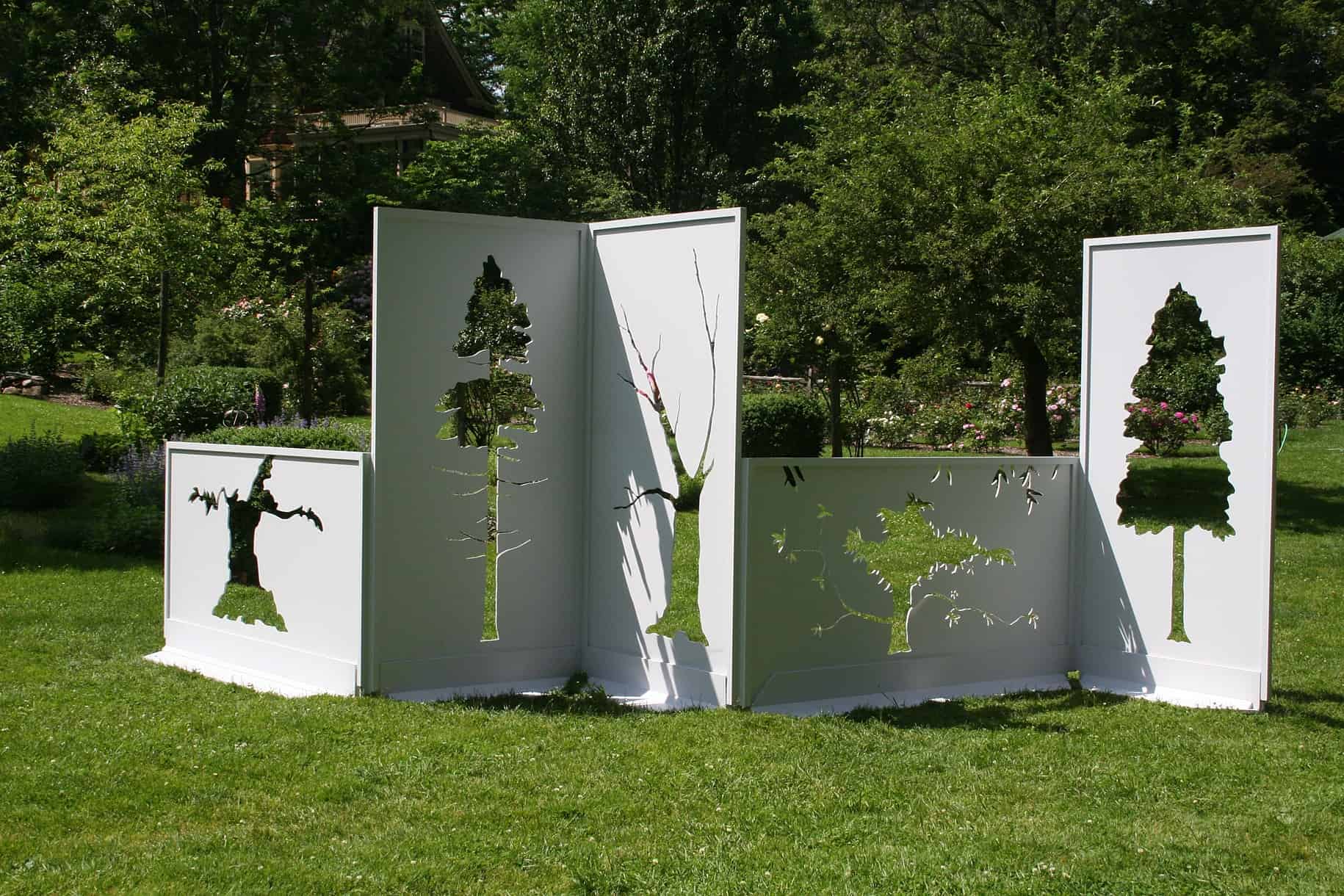

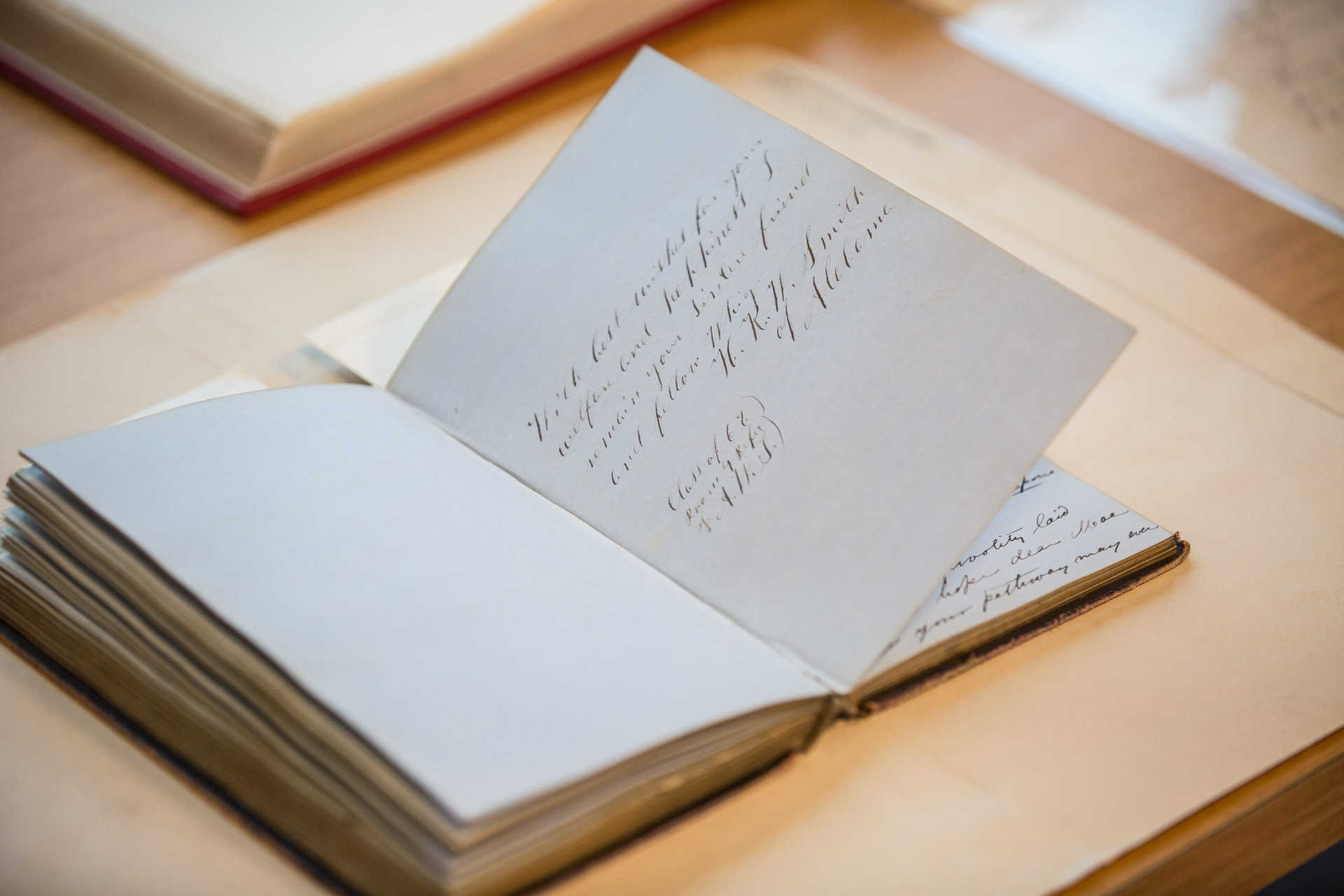

The entrance to “Dreaming of Utopia” at Morven features a large-scale reproduction of the Shahns’ mural. Also on display are Otto Wester’s futuristic aluminum doors created for the community center, which depict the field and factory workers of Jersey Homesteads and, in the distance, the skyscrapers of a city. The exhibition’s engaging wall panels give the town’s history, illustrated by photographs of the first settlers, houses being built, workers on the job, and more. Objects on display include an original handwritten receipt for $500, the amount a prospective settler had to put down to reserve a place in the new town.

The galleries include work by Roosevelt artists up through the 2010s. Of special note are two busts, or “heads” by sculptor Jonathan Shahn, who has lived in Roosevelt since he was a year or two old. The first greets visitors at the entrance to the show; it’s a replica of an enormous head of Franklin D. Roosevelt located in a park near the Roosevelt school. It became the first public memorial to the president in the United States when it was dedicated in 1962, in a ceremony attended by Eleanor Roosevelt.

The second, placed in the final gallery of Morven’s exhibition, is a plaster study of the head of Martin Luther King, Jr., created by Shahn in preparation for a Civil Rights Memorial in Jersey City. The final sculpture was commissioned by the New Jersey State Council on the Arts Transit Arts Committee, and dedicated in 2004.

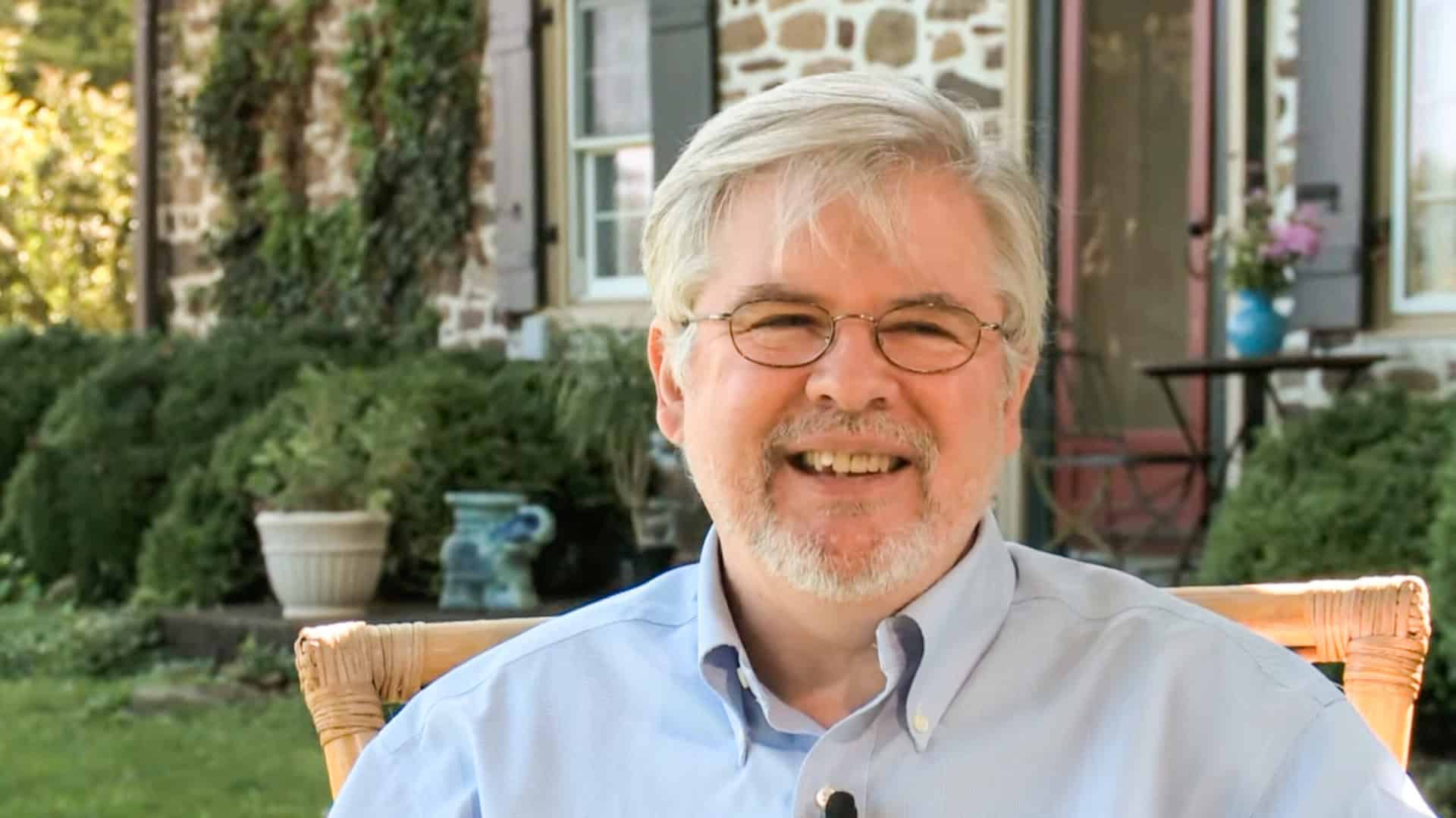

“Dreaming of Utopia” is an ambitious, unusual exhibition. It features not a single artistic style or medium, but a diverse community of artists, connected by their experience of living and working in Roosevelt. It was conceived and orchestrated by Elizabeth Allan, Morven Museum’s deputy director and curator, and Ilene Dube, writer and guest curator. Dube first became familiar with Roosevelt and its community of artists in the 1990s, when she was an editorial director at “Time Off.”

“I was just fascinated by the fact that subsequent generations of artists were continuing to this day,” says Dube. She was inspired to make a short film, “Generations of Artists: Roosevelt, NJ,” and, ultimately, to guest curate the exhibition now at Morven.

The opening of “Dreaming of Utopia” was a homecoming for Rooseveltians who have moved on, and a steady stream of locals are visiting to see the history of their town and its artists honored. But the meaning of a place like Roosevelt speaks to a wider audience. Not only were many of the artists well known, even famous in their day, but Roosevelt was founded on an ethic that intertwined labor, art, and social responsibility.

“What I find so exciting,” says Dube, “is that the issues that concerned the artists working in Roosevelt back in the 1930s are still so relevant today — civil rights, economic equality, immigration, labor issues and fair pay, the right to free speech, and women’s reproductive rights.” In today’s polarized world, many artists are returning to social and political themes. “Dreaming of Utopia: Roosevelt, New Jersey” serves as a history lesson about a place where another path was taken, and where progressive politics, art, music, and the value of a simple life continue to flourish.

To find out more about Roosevelt’s history and its artists, “Dreaming of Utopia: Roosevelt, New Jersey” at Morven Museum & Garden in Princeton is a first stop. The exhibition is on view through May 10, 2020. Next, visit the Roosevelt Arts Project for upcoming community events, concerts, and tours.

![Truckdriver after a Run, Ohio, Sol Libsohn, 1945 [ICP]](https://stateoftheartsnj.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/libsohn_sol_156_1983_411582_displaysize.jpg)